Have you ever given your child a direction that is met with a blank stare or an excessive delay before he or she follows it?

Does it happen even after you make sure that the Candy Crush game is put away and you have your child's undivided attention? It might not be that he or she is ignoring your request; it may actually be a reflection of your child's ability to process the language used before he or she can initiate or complete the task. Receptive language (the ability to comprehend language, or follow directions) and expressive language abilities (the ability to formulate language to complete written or spoken academic work) are inextricably linked with executive function skills.

Does it happen even after you make sure that the Candy Crush game is put away and you have your child's undivided attention? It might not be that he or she is ignoring your request; it may actually be a reflection of your child's ability to process the language used before he or she can initiate or complete the task. Receptive language (the ability to comprehend language, or follow directions) and expressive language abilities (the ability to formulate language to complete written or spoken academic work) are inextricably linked with executive function skills.

As a speech-language pathologist and an academic coach, I find myself thinking about language and executive function skills a lot. It’s to the point where all of my friends are sitting on the beach reading gossip magazines about the latest Bachelorette news and I bring along a stack of magazines to read the latest speech and language news and research.

As I take a break from my beach reading stack, I reflect about the progress my students made over the past school year, and I am reminded about the relationship between executive function skills and language. During one recent session, my student and I planned an essay. He used a graphic organizer to plan and organize the format of his essay but had considerable difficulty generating content and even following my directions to write down the content we formulated together. This session got me thinking about my academic coaching toolbox, or “go to” strategies to help students with both language and executive function challenges. I thought I would share with you 3 of my favorite strategies.

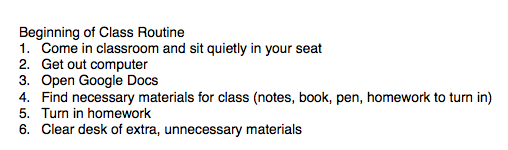

1) Pair verbal directions with written directions

Pairing a verbal direction with a written direction gives children something tangible to refer back to without straining their working memory capacity (that is, memory that is temporarily stored and manipulated - think multiplying two-digit numbers in your head). In addition, a written direction is the perfect opportunity to practice following directions to ensure comprehension. For example, your child can circle or highlight key parts of the direction and you can check in to make sure he or she understands the expectations. Written directions are beneficial for a variety of tasks, ranging from following a beginning of class routine to completing homework or practicing essay questions.

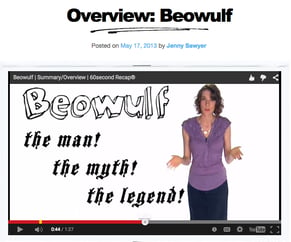

2) Technology is your friend...really

I know. I know. There is a constant debate about whether kids are too tuned in to their devices. I frequently hear from the parents of students I coach that their children lost technology privileges because they spent too much time playing Minecraft rather than completing their homework. With that being said, iPad applications like Educreations (white board application where you can create a study guide) or websites like 60 Second Recap or Shmoop (study guide websites) or Quizlet (online flashcard generating site) are effective tools for active studying for tests. Why read Sparknotes when you can watch quick, fun and engaging videos?

I know. I know. There is a constant debate about whether kids are too tuned in to their devices. I frequently hear from the parents of students I coach that their children lost technology privileges because they spent too much time playing Minecraft rather than completing their homework. With that being said, iPad applications like Educreations (white board application where you can create a study guide) or websites like 60 Second Recap or Shmoop (study guide websites) or Quizlet (online flashcard generating site) are effective tools for active studying for tests. Why read Sparknotes when you can watch quick, fun and engaging videos?3) Keep a folder of helpful resources to promote independence

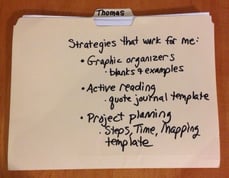

There is no need to reinvent the wheel here. If your child has been successful with graphic organizers or other note-taking strategies, keep examples of both blank and completed handouts in a readily accessible folder (paper or digital, as your child prefers). In the initial stage, work with your child to compile the resource binder as a way to reflect about successful strategies as well as those that were not beneficial. As your child becomes more confident and independent, refer him or her to the folder to access strategies without hounding your child. Strategy folders can be added to or modified to meet the evolving needs of your child.

There is no need to reinvent the wheel here. If your child has been successful with graphic organizers or other note-taking strategies, keep examples of both blank and completed handouts in a readily accessible folder (paper or digital, as your child prefers). In the initial stage, work with your child to compile the resource binder as a way to reflect about successful strategies as well as those that were not beneficial. As your child becomes more confident and independent, refer him or her to the folder to access strategies without hounding your child. Strategy folders can be added to or modified to meet the evolving needs of your child.

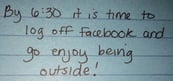

So the next time your child has difficulty following your directions to get off Facebook and go outside, try  slipping him or her a post-it note with your written request (and the time it should be completed by) along with your verbal direction. That may very well provide the extra language input to help your child successfully respond. That’s a win for both of you!

slipping him or her a post-it note with your written request (and the time it should be completed by) along with your verbal direction. That may very well provide the extra language input to help your child successfully respond. That’s a win for both of you!

Ready to start your own resource folder of strategies for your child? Download our project planner template below.

Lindsay Schelhorn, M.S., CCC-SLP is an executive function coach and a certified speech-language pathologist. She currently works as a speech-language pathologist at the Clearway School in West Newton, MA. After completing her bachelor's degree in Psychology at Gettysburg College in Pennsylvania, Lindsay completed a graduate certificate in Autism Studies at West Chester University in Pennsylvania. She graduated from Mass General Hospital’s Institute of Health Professions with her degree in Communication Sciences and Disorders. She feels passionately about guiding teenagers and young adults to becoming more independent by increasing their confidence in functional skills, and teaching them strategies to increase their understanding and awareness of the relationship between social skills and executive functioning skills.