When you work out your body, it’s usually because you’re looking to drop some fat. But when you  work out your brain, you’re actually gaining some extra fat.

work out your brain, you’re actually gaining some extra fat.

Don’t worry, it’s not likely to register when you step on your scale. This fat operates at the microscopic level to help lock in skills and routines. How does your brain help you create better study habits? Well, here’s a simplified view.

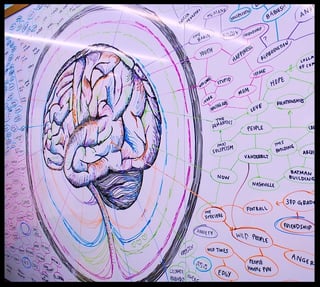

How your brain forms a habit

The brain is full of neurons - between 85 and 100 billion. And, for the most part, memories and skills that you’ve acquired over time are associated not just with one neuron, but with a network of neurons. It’s a network because these neurons are connected by axons (long, slender nerve fibers). It’s the axons’ job to allow neurons to communicate by conducting electrical signals between them. When you perform an activity over and over again — developing a habit like using a homework planner or practicing a skill like writing an organized paragraph — your brain coats the axons in the associated neural network with a fatty substance called myelin (in a process aptly named myelination).

Essentially, the myelin - the brain fat - acts as a resistor and current director, helping the neural impulses to flow along a preset path. It’s similar to how a channel helps to direct the flow of water. It keeps it flowing in the same direction, rather than spilling out inefficiently. Myelin works in much the same way. It insulates the axons within the neural network to improve the flow of signals between the neurons. In other words, it creates a preset channel for your brain signals to quickly and easily flow through.

What your brain fat does for you

These brain fat channels are what allow our brains to learn complex skills. A 2005 study of expert musicians showed, unsurprisingly, that these experts had more myelin than average in areas of the brain related to finger dexterity and auditory processing. More interestingly, by surveying the musicians on their practice history, the study showed that myelin was created more quickly during their early years of practice — likely because kids’ brains pick things up more rapidly.

In addition to polishing practiced skills, those myelin-insulated axons make habits easier to do. In fact, they can allow complicated routines to be done automatically, without conscious input. (Think about when you get up to use the bathroom in the middle of the night and you unconsciously know where to put your hand to turn the light on. That’s myelin working for you.) The benefit of that automatic processing is that it frees up your brain’s processing and your willpower to work on other things (like figuring out what the dream that woke you up - where your hands turned into ice cream cones - really meant).

What brain fat means for students

Learning how to operate the brain’s automatic processing can help students make tasks a lot easier. But, as anyone who has made a New Year’s resolution knows, you can’t create a new habit merely by wanting to. The trick is in picking the right cues and rewards to help your brain get that myelin right where you want it. The cue is the thing you see or smell or feel that makes you start the habit, while the reward is what you feel after completing the habit.

Much of the work that I (and my fellow Executive Function coaches) do with students relies on this habit-forming process. For example, I love to work with timers and chimes. When I'm coaching a student who has a hard time getting work started, I’ll suggest a strategy intended to help that student build a routine for initiating work. I'll demonstrate by telling him that we will be starting a 20-minute work cycle five minutes from now. I’ll set a timer for five minutes, and when the chime from that timer goes off, that’s the cue to start. My student benefits from that 5 minutes of ramping up time as he gets his brain into work mode. When the twenty minutes of work is up, the chime announcing its end (and the start of the short break that follows) is the reward. When I coach a student who has trouble remembering to pass in her completed homework, we may use a brightly colored homework folder (the visual cue) that has work "to do" on one side and work to turn in on the other side. The reward is getting credit for her hard work from the teacher.

The process is adaptable, but the structure is the same: Set (or discover) a cue for the behavior you want to start, and make sure the brain receives a small reward for completing the routine. It takes time and consistent repetition of the habit in order for the myelin to form, which is why it can help to have a coach guiding a student along the way. That’s what Executive Function coaches do. We work to help students discover and practice better work habits, so that, over time, the myelin in the brain takes over. We’re like personal trainers, only instead of helping you cut fat, we help you add it (to your brain, that is).

Dan Messier is an Executive Function coach with Beyond BookSmart from Holbrook, MA. He received his bachelor's in English from Eastern Nazarene College in Quincy, Mass., and his master's in English composition from the University of Massachusetts Boston, where he has taught first-year writing as a member of the English department since 2010.

Dan Messier is an Executive Function coach with Beyond BookSmart from Holbrook, MA. He received his bachelor's in English from Eastern Nazarene College in Quincy, Mass., and his master's in English composition from the University of Massachusetts Boston, where he has taught first-year writing as a member of the English department since 2010.

Does your child need to build better habits to manage materials? Download our helpful guide, Strategies for the Forgetful Student.

photo credit: derekbruff Stream of Consciousness via photopin (license)