Editor's note: This week, we feature Mandi Croft-Petoskey and Amanda Moons of Neuro Educational Specialists.

If your child is struggling in school, a neuropsychological evaluation can provide insight into where an intervention might be helpful.

Now that the routine of another school year has settled in, parents and children are shifting their focus to how to make the most out of this new school year. And while learning algebra equations and science facts are undoubtedly part of the school success formula, research is highlighting the importance of Executive Functioning (EF) skills over IQ scores as a predictor of students' achievement. EF skills encompass a broad array of abilities, from attention and impulse control - to working memory, organization, time management and more. A comprehensive neuropsychological evaluation will identify both strengths and weaknesses of a child's EF skills. From there, we can choose an appropriate intervention, to work on strengthening any EF skills which may need improvement.

their focus to how to make the most out of this new school year. And while learning algebra equations and science facts are undoubtedly part of the school success formula, research is highlighting the importance of Executive Functioning (EF) skills over IQ scores as a predictor of students' achievement. EF skills encompass a broad array of abilities, from attention and impulse control - to working memory, organization, time management and more. A comprehensive neuropsychological evaluation will identify both strengths and weaknesses of a child's EF skills. From there, we can choose an appropriate intervention, to work on strengthening any EF skills which may need improvement.

Brain Development and Executive Function

In order to best support the development of EF skills for our children and adolescents, it's helpful to have some background knowledge about brain development. The brain develops from the back to the front and EF skills are housed in the frontal lobe of the brain. Research suggests that the brain continues to develop until we are in our late 20s, highlighting that EF skills are among the last skills to fully mature. In the brain, the ability to use EF skills to hold onto and work with information, focus and filter distractions, and switch tasks is quite complex! Acquiring and building the foundation for EF skills is one of the most important and challenging tasks of the early childhood years.

Which Executive Function skills are developmentally appropriate?

An infant’s interaction with an adult can help set the stage for the earliest development of EF skills like attention, working memory, and emotion regulation. This can be done through playing games, engaging in role play, or singing songs with simple hand motions. As infants enter into toddlerhood, their language skills expand and play a large role in their ability to develop their EF repertoire. Adults can help toddlers develop language skills through active games, storytelling and conversations, matching or sorting games, or imaginary play. As a child reaches the end of toddlerhood (around 3 years old), their EF skills begin to develop and grow rapidly. Children at this age begin to gain more independence from adults to apply skills like attention, impulse control, and working memory. This can be done through more elaborate imaginary play, such as a pretend doctor's office visit, gross motor or movement challenges, such as Simon Says, or quiet games and activities like puzzles, card and board games, or cooking. As children get older, they benefit from playing games that involve more reflection and strategy, such as chess, Minecraft, or Dungeons and Dragons.

At times, adults can place demands on adolescents that are beyond their developmental level. For example, assigning a science fair project where they need to independently set realistic goals and continually self-monitor progress can be very difficult for some teens without the support and guidance of an adult. Complex areas such as planning, study skills, test taking strategies, time management, and monitoring their own behavior are all part of an adolescent's landscape. However, it is important to remember that adolescents often are unable to do these on their own and benefit from adults teaching them how to best go about these activities.

Throughout all of these developmental stages, metacognitive skills (the ability to think about one's own learning and thinking) are evolving, which help students make good decisions about how they approach their schoolwork, based on a deep self-knowledge.

What does a comprehensive neuropsychological evaluation look like?

If you are concerned about your child’s EF skills, a comprehensive neuropsychological evaluation can help shed light into what is going on and how to help. The purpose of the evaluation is to identify your child’s unique pattern of strengths and weaknesses in the areas of cognitive functioning, information processing, memory, learning, executive functioning, academic achievement, and social-emotional functioning. When specifically evaluating EF, it is best practice to have a psychologist conduct parent and teacher interviews, behavior observations, behavior rating scales, along with formal standardized assessment. This combination of information will illuminate specific EF weaknesses (i.e., task initiation, sustained attention, cognitive flexibility) and real-life challenges likely affected by the deficits (i.e., problems with following directions, organizational skills, handling long-term assignments, homework completion). The collective goal of gathering all of this information is to determine how it manifests in real life in both the home and school environments, and then, most importantly, where and how we can intervene. A comprehensive neuropsychological evaluation should not only highlight specific EF weaknesses, but also report on cognitive strengths that can be used to help compensate for the weaknesses. For example, if a child has strong visual spatial abilities, then it will be critical to employ an intervention with a great deal of visual aides and supports.

How to link an Executive Function assessment to specific interventions

A complete neuropsychological evaluation should identify if the EF weaknesses are skill-based or performance-based. A skill deficit means the student does not know how to perform the desired behavior, while a performance deficit means the student knows the skills necessary to perform the behavior, but does not consistently use them. Skill versus performance deficits can be uncovered in the course of testing and can help guide the interventions that a child may need. For example, if a child has skill deficit with fluently recalling math facts, an appropriate intervention here would center around finding motivating, engaging ways to repeatedly practice math facts until they become automatic. A performance-based deficit is when the core skill is found to be intact in testing, yet the student struggles to apply this skill in their schoolwork. Intervention at this level would focus on identifying factors that prevent the student from applying that skill. For instance, if intact math skills were identified in the evaluation, yet the child is struggling in math class, perhaps the student has attention challenges that affect their ability to focus in the classroom environment.

An important component of any intervention is that it's implemented with fidelity and that there is support provided at home and school. It is also key to work on interventions in the context of students' schoolwork in order to help them generalize their learning. The more meaningful the intervention, the more likely the student will be motivated and prepared to use it in multiple contexts. There is not a universal approach or a quick fix; improving EF is a process that takes time. Every strategy must be individualized and tailored specifically to fit each child’s needs. The human brain is malleable and has an immense capacity for learning. It is possible to improve the Executive Functions of children with comprehensive assessment, targeted strategies, guided practice, and adult support.

Photo above by Zach Lucero on Unsplash

Mandi Croft-Petoskey, Ed.D., NCSP, ABSNP is an Illinois licensed and nationally certified School Psychologist. Dr. Croft earned a doctoral degree in School Psychology with an emphasis in Neuropsychology from The Chicago School of Professional Psychology. Dr. Croft is the founder of Neuro Educational Specialists and specializes in neuropsychological evaluations. She spearheads initiatives with both private individuals and school districts to integrate neuropsychological and educational principles of assessment and intervention with children and adolescents.

Amanda Moons is an Illinois licensed and nationally certified School Psychologist. She earned a Masters in Education and an Educational Specialist Degree from National Louis University and a Masters in Educational Leadership from the American College of Education, after receiving her Bachelors degree in Psychology from the University of Illinois. Amanda has worked in the field of education for 16 years in the northern suburbs of Chicago. She conducts evaluations at Neuro Educational Specialists.

Amanda Moons is an Illinois licensed and nationally certified School Psychologist. She earned a Masters in Education and an Educational Specialist Degree from National Louis University and a Masters in Educational Leadership from the American College of Education, after receiving her Bachelors degree in Psychology from the University of Illinois. Amanda has worked in the field of education for 16 years in the northern suburbs of Chicago. She conducts evaluations at Neuro Educational Specialists.

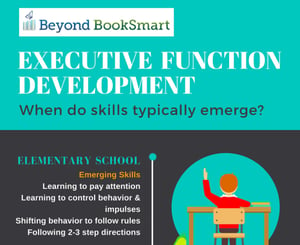

Download our colorful infographic that describes a timeline of typical Executive Function skill development from elementary school through adulthood.

Download our colorful infographic that describes a timeline of typical Executive Function skill development from elementary school through adulthood.