Editor's note: This week, we feature guest blogger Elizabeth Hamblet, a learning consultant in Columbia University’s disability services office. Please see her full bio below.

“I honestly don’t know.” The student is looking at a grid showing the days of the week broken into  hour blocks that she’s filled in with her classes, sleeping and meal times, and rehearsals. This is her response when I ask her what she did in all of those empty blocks representing unscheduled time instead of her work. And it’s true – she really doesn’t know how she spent those free hours. I get it.

hour blocks that she’s filled in with her classes, sleeping and meal times, and rehearsals. This is her response when I ask her what she did in all of those empty blocks representing unscheduled time instead of her work. And it’s true – she really doesn’t know how she spent those free hours. I get it.

As a learning consultant at a university’s disability services office, I go through this exercise with numerous students each semester, regardless of their area of difficulty. This is because time management and the executive functioning demands that accompany it present challenges for many students at college, where the lack of structure presents serious challenges.

Why do college students, who typically only have to be in classes 12-15 hours a week, have trouble completing their work on time? The explanation is fairly simple: the large amount of free time they have makes it hard to get down to work because it seems like they can do it at any time, which leads to procrastination. Many adults should be able to relate to this. We often don’t accomplish what we expect to during the weekend when we have lots of free time because there’s no consequence for not getting through our to-do list — unless it involves a consequence like incurring a charge for a late bill payment.

It is a similar lack of accountability in the college environment, combined with a lack of immediate consequences, that trips up many students. Professors don’t typically give reading quizzes or probe students’ understanding of reading materials each time classes meet, so it can be hard to feel an urgency to do the readings. The consequences of procrastination become obvious right before midterms, when panicked students try to read numerous chapters of a book before they can even attempt to study the material. Of course, for students with a variety of learning and attention issues, the procrastination can be a bigger problem because they take longer than their peers to get through readings. This puts them even more at risk for not getting through all of the materials before the test. And while they may get extended time for exams (a commonly-granted accommodation for students with disabilities) it won’t help if they don’t know the material. In sum, the low midterm grade that may result from cramming is too far-away a consequence to keep students focused in the weeks between the start of the semester and midterms.

Exams aren’t the only situation where poor time management can be a problem – papers can be, too. Students often have at least a week to write their papers and professors don’t typically check their progress – they just want the final draft. And while students with learning and attention issues may have had extended deadlines for their papers in high school, many will not get this accommodation at college. IEPs and 504 plans aren’t valid at college, and colleges don’t have to provide every accommodation students received in high school. Even when they manage to persuade a professor to give them an extension, many students still don’t start that paper until the night before the extended deadline, anyway.

I point out to students that procrastination is truly to be expected in this environment and that they should stop feeling guilty about it. Some students with learning and attention issues already feel guilt and shame. However, if they are unhappy with the results, they can take action to avoid unpleasant consequences in the future. This means making a plan.

Creating a weekly schedule at the beginning of the semester gives the week structure and takes away the constant need to decide what to do next (i.e., prioritize), which can be draining and lead to unproductive choices. Students plan when they’ll complete work for each course, making sure that they have allotted enough time for each class’s readings and assignments. Creation of the plan includes discussion of when they are most productive (morning? evening?) where they should study (library vs. dorm room), and how they can create accountability for completing those study blocks (meet a friend at the library but sit at different tables). Many students see that they still have free time for social activities, and I remind them that when there is a paper due, they need to fill up those blocks by working on it. I also encourage students to start the semester by putting all of their exam dates and paper deadlines on their calendar - plus reminders about these, beginning two weeks before these dates - to keep them “on their radar.” And as those paper deadlines approach, we break the assignments down into interim deadlines.

No plan is perfect, so I tell students to adjust theirs after the first week, adding or eliminating study blocks according to how much time they find they need. I also remind them that life is unpredictable and that the reason they should plan to do work a few days ahead of time is to allow for unforeseen events. I encourage them to view this schedule of study blocks as a Jenga tower. If they have to give up a scheduled study block for something, they should visualize this as removing a block from the tower and look at their schedule for an empty block where they can reinsert the block to keep the structure of their schedule intact. This helps to keep them on track.

College is an exciting place but it can be a challenge. Emphasizing the importance of planning can help students have a more successful semester at college.

Elizabeth C. Hamblet, a learning consultant in the disability services office of Columbia University, has worked at the college level for twenty years. In addition to her work with students, she is a nationally-requested speaker on the topic of how to prepare students with disabilities for success at college. Ms. Hamblet is the author of From High School to College: Steps to Success for Students with Disabilities, and her work has appeared in numerous journals. She offers information and advice on her website, www.LDadvisory.com. She can be found on social media at www.facebook.com/LDadvisory and on Twitter @echamblet.

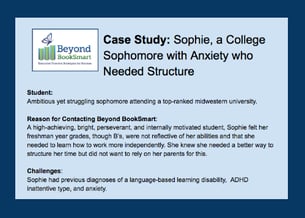

Click the green button below to discover how Executive Function coaching helped Sophie, an anxious college student who needed to learn how to structure her time and gain confidence in her writing skills.