Allow me to set the scene: Alison - a high school student with ADHD - is working on a 5-paragraph essay for a book she was less than thrilled to read. She’s finished the book, we’ve got a solid grasp of the prompt, and now she’s stuck. Casually, I ask her, “How does this book compare to something else you’ve read before?” This leads her to launch into a full-out discussion about Hazel Grace - a main character in a book she actually likes, called The Fault in Our Stars:

than thrilled to read. She’s finished the book, we’ve got a solid grasp of the prompt, and now she’s stuck. Casually, I ask her, “How does this book compare to something else you’ve read before?” This leads her to launch into a full-out discussion about Hazel Grace - a main character in a book she actually likes, called The Fault in Our Stars:

“Oh my gosh, the main character reminds me so much of the pain that Hazel goes through! I mean, like, she has cancer and thinks she’s going to die, but she still does complicated stuff like taking college classes and trying to have a relationship. It’s so pointless when you think about it because she’s so sick, but like, I can see how school and her boyfriend would keep her motivated to live. Like, when I think about it, I can’t understand why she does it and I totally can at the same time, you know?”

As she turns to me with this question, one thing is clear: Alison’s mind is fully submerged in another book. And just as quickly as I mumble an “mmhmm” of agreement, she launches elsewhere:

“My friend Zoe is also in a relationship with someone that I understand and don’t at the same time. I also haven’t bought Zoe her birthday gift yet and it’s this Friday -- OH-MY-GOSH-IT’S-FRIDAY -- I have three ideas for it I just need to get a ride to the mall.”

Feverishly, she grabs her phone and texts her dad if he can drive her on Thursday. The computer screen - onto which her 5-paragraph essay should be blossoming - has a screen saver soaring over it.

For Alison, and many other students with ADHD, this line of thinking is quite common. When I ask Alison, “How did we start talking about your friend’s birthday gift?” she looks at me blankly, as if unable to retrace those steps back to the work at hand. I give her a minute to reflect, and her eyes eventually track back to her screen. She returns to the point of departure, but another derailment is on the horizon.

Alison’s tangential train of thought is common for people who experience ADHD inattentive type. Her inability to sustain focus on an assignment prolongs her homework time frame, often pushing past midnight and affecting her sleep, which then affects her performance in school the next day. Alison’s parents are at the point where they’re interested in exploring medication. As academic coaches who work with hundreds of students each day, we realize that this is not a path that every family chooses, and we acknowledge and work on alternative strategies to help students with ADHD. However, for parents who are considering medication, here are 3 ways Executive Function coaches support students with ADHD who are trying medication for the first time.

1) Set Alerts

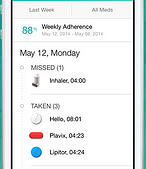

Alison and I set up the app MediSafe on her phone. This app shows four screens for time zones in the day: morning, noon, evening and night. When you select a medication, it puts an actual graphic of what that pill looks like into the appropriate zone:

2) Develop Awareness

Simply adhering to a consistent schedule for taking medication doesn’t mean all problems are solved. Alison also needs to evaluate how helpful the medication is in improving her sustained attention. The first thing we did was record some observations and feelings for a few weeks prior to beginning the medication routine using a graph like this:

| Day | Task | Time Needed | How I Felt | Lost Attention |

| Mon. | 5-paragraph essay | 3.5 hours | stressed, tired, bored, could not just get to work | Caught myself daydreaming and going onto social media 7 times. Also my dad caught me texting twice. |

We then made a similar table for the medication trial. By helping Alison become more mindful of her actual experience when doing homework on medication and off of it, she collected data that was useful for her to look back at and for her to bring to doctor appointments.

3) Strive for Independence

Coaching Alison through this new element of ADHD management makes it clear that knowing something is helpful to you doesn’t automatically mean you’re going to do it. When your child discovers effective strategies for managing attention - medicinal or otherwise - setting up visual and auditory reminders and charting progress are great first steps to turning an advantageous action into a helpful habit.

Looking for non-medicinal strategies to help your child focus attention more effectively? Click below to download our Focus Formula survey and worksheet.

Brittany Wadbrook is a college instructor, certified writing tutor, and senior Executive Function coach at Beyond BookSmart. She began her career in education at Quinnipiac University earning a bachelor of Arts in English and Masters degree in Secondary Education. While at Quinnipiac, she became a certified Master Level Writing Tutor by the College Reading and Learning Association and spent three years working for the University's Learning Center. Feeling motivated to expand her pedagogical skill set, Brittany pursued a second Masters degree in Composition and Rhetoric at the University of Massachusetts Boston. After graduating, she became a full-time lecturer at UMass where she currently teaches first-year composition to a diverse classroom culture including English Language Learners and nontraditional students from a variety of academic backgrounds. Brittany's experience with adult learners, diverse cultures, and a range of learning abilities has enabled her to become a flexible educator who is sensitive to individual learning needs and intrinsically invested in their educational success.

photo credit: Steven Leonti via photopin cc