Put yourself in your student's shoes: You’ve got an essay due in a week, and perhaps you’re not particularly looking forward to it. You set up your study space, turn on your computer, open a blank document, curl your fingers over your keyboard, and…nothing. You’ve got nothing.

perhaps you’re not particularly looking forward to it. You set up your study space, turn on your computer, open a blank document, curl your fingers over your keyboard, and…nothing. You’ve got nothing.

If the above is a familiar situation, you might be experiencing a bit of horror vacui, a fancy term for the “fear of empty space.” Maybe writing feels like a huge task, and you’re not sure how to break it down. Maybe you believe the sentences of your essay have to be perfect—exactly what you mean to say straight from your head to the page. Maybe you spend hours trying to craft the perfect sentences so you don’t have to go back and revise.

Whatever the case may be, here’s the deal: your writing will not be perfect. When you get your ideas down on paper for the first time, you will not have a masterpiece. Your effort should not be akin to Michelangelo painting the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel (which took him four years to finish!). I hereby give you permission to start the writing process by writing a messy, disorganized paper.

Use Drafts to Chunk Your Workload

It turns out I’m not the only one who is giving you permission to do this. In her essay “S****y First Drafts,” novelist and writing teacher Anne Lamott encourages us to think of writing less as a task and more as a process. With a nice dose of humor, she chunks this process by talking about papers in terms of drafts:

"Almost all good writing begins with terrible first efforts. You need to start somewhere. Start by getting something—anything—down on paper. A friend of mine says that the first draft is the downdraft—you just get it down. The second draft is the up draft—you fix it up. You try to say what you have to say more accurately. And the third draft is the dental draft, where you check every tooth, to see if it's loose or cramped or decayed, or even, God help us, healthy."

Yes, this does mean that you need to look over your work a few times before turning it in. It means you can’t delay until the last minute to start writing. It doesn’t mean that you’re rewriting your paper multiple times; rather you’re committing to going back and improving your original draft. Doing so means there isn’t as much pressure to create a beautiful paper the first time around.

Start by Beginning.... (yes really!)

This might sound oversimplified, but you begin by beginning. For what Lamott calls the downdraft and what others might call a brainstorm, set yourself a 15-minute timer and start writing anything that comes to mind. Some people like to copy the prompt and leave it at the top of their page for reference. Then think about what kinds of sources you might use to support your answer to the prompt. The thoughts and ideas you come up with don’t need to be written in a particular order.

This is your permission to be messy, to be creative with your ideas. Feel free to use bullet points. If physically writing something into a notebook is more your style, do it. If you’re a hands-on learner, use sticky notes and attach them to your wall. In the first draft, grammar errors and run-on sentences are not a problem. In the next draft, you can separate everything out into intro, body paragraphs, and conclusion, and smooth out your sentences.

Make Use of Breaks

If while writing you find yourself getting stuck, get up and get moving.* It’s been found that exercise that gets your blood moving can improve your memory. According to a 2014 New Yorker article, there’s a special connection between mind and body that can lead us to mindfulness:

Walking at our own pace creates an unadulterated feedback loop between the rhythm of our bodies and our mental state…When we stroll, the pace of our feet naturally vacillates with our moods and the cadence of our inner speech; at the same time, we can actively change the pace of our thoughts by deliberately walking more briskly or by slowing down.

Not only can walking help improve our ability to self-regulate, but the article also goes on to say that that walking primes us for creativity: “Because we don’t have to devote much conscious effort to the act of walking, our attention is free to wander…This is precisely the kind of mental state that studies have linked to innovative ideas and strokes of insight.” People who write for a living have said similar things: one author remarks that her daily walk “simply puts some ‘useful distance’ between her and the work.”

So allow yourself some time away from your drafts. Write a draft, and come back to it a couple of hours later or the next day. Giving your body exercise and your brain time to focus on something else will boost your ability to write your paper.

A note for those of us who tend toward procrastination: Taking breaks is not an invitation to stop working every time you start getting distracted. Instead, make a plan of attack for your writing assignment that includes a break or two, and stick to your plan. Set a timer to guide you through your work sessions and your breaks. If you find your mind wandering, or start to feel the itch to check your phone or watch a quick YouTube video, it might be useful to reread the draft you’re working on (aloud, if possible) to recenter your attention. Your timer will let you know when it’s time for a break.

Fix Things Up

What Lamott calls the dental draft is the final look-over at your paper. Here’s where spell-check is useful, as is the practice of reading your paper aloud. Sometimes, it’s only when we read our papers to ourselves that we catch little errors that even our computers didn’t catch. Sharing your paper with a trusted adult or sibling to get another set of eyes on your paper can also be a great practice. Just remember that if you ask for help, you’re also saying you’re open to their feedback.

where spell-check is useful, as is the practice of reading your paper aloud. Sometimes, it’s only when we read our papers to ourselves that we catch little errors that even our computers didn’t catch. Sharing your paper with a trusted adult or sibling to get another set of eyes on your paper can also be a great practice. Just remember that if you ask for help, you’re also saying you’re open to their feedback.

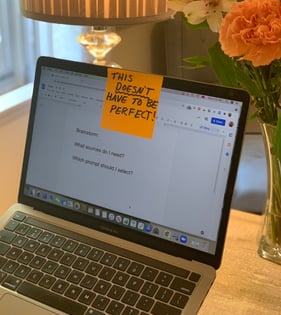

Though the writing process can feel a bit daunting, I suggest that you create a ritual around it. Make yourself a comforting snack or drink (like a mug of tea or hot chocolate), play quiet, wordless music (if it’s not distracting to you), and turn off your phone. Then take out a sticky note and write, “This doesn’t have to be perfect.” Stick it to your computer and repeat it to yourself when you’re feeling stressed. When you give yourself permission not to be perfect, your papers will be a lot less painstaking to write and may even be a more pleasant experience than you could have imagined.

Photo (directly above) by Brett Jordan on Unsplash

Lindsey Weishar is a freelance editor and writer, as well as an executive function coach for Beyond BookSmart. She possesses an MFA in Creative Writing and Media Arts from the University of Missouri-Kansas City, and has seven years of teaching experience in the following settings: high school special education classes (as a paraprofessional), college-level writing classes, and adult-level literacy and English language classes. Her mission is to help individuals more greatly delight in reading and writing.

Perfectionism can derail a student's productivity. Learn how summer coaching can help your student cultivate effective habits by applying Executive Function strategies within a context that's personally meaningful.