“If I don’t wash the towels, then make up the lunches, then go get ice for the cooler, and pack the car up tonight, we’ll never get out the door and to the beach tomorrow.” This is just the sort of thing my friend Dylan would say as he prepares for Cape Cod traffic in the summer. Usually, I reply with something like: “Could Geoff help you with some of that?” Dylan laughs and rolls his eyes as he reminds me that Geoff is the reason he needs to do all of that prep work himself.

cooler, and pack the car up tonight, we’ll never get out the door and to the beach tomorrow.” This is just the sort of thing my friend Dylan would say as he prepares for Cape Cod traffic in the summer. Usually, I reply with something like: “Could Geoff help you with some of that?” Dylan laughs and rolls his eyes as he reminds me that Geoff is the reason he needs to do all of that prep work himself.

Dylan’s husband Geoff is a lot of wonderful things: a caring spouse, a dedicated dad, a creative writer, and a reliable helping hand when you’re moving. But for all his great qualities, it regularly irritates Dylan that he rarely plans ahead, frequently forgetting things he needs and arriving late to most places he needs to get to.

But I’m not here to talk about Geoff and how he might improve his planning and on-time arrivals. I’m here to talk about Dylan. And how everything he’s doing in an effort to make up for Geoff’s Executive Functioning (EF) deficits actually prohibits him from growing his skills (and keeps him in a perpetual cycle of stress).

Dylan knows that since Geoff is in his mid-thirties, his frontal lobe development is complete. But that doesn’t mean that Geoff is doomed to spend the rest of his life failing to plan and frustrating his spouse. Neuroplasticity is a reason why we are able to develop and sustain new habits as new pathways and connections are formed and/or reorganized in the brain. This means that the routine of Dylan doing most of the work continues to reinforce it for him, making it seem easy or natural. But it’s also the reason it’s such a struggle for Geoff; he hasn’t deliberately worked on neural remapping to enhance his Executive Functioning.

Carrying the Weight vs. Dividing the Labor: Recognizing a Potential Issue

In many relationships, each person has different strengths and weaknesses when it comes to their Executive Functioning. Because of this, partners often work as a team, helping each other out in productive ways. But there’s a fine line between being in a supportive, symbiotic partnership where the EF labor is helpfully divided and being the support system for all parties involved. Determining whether you’re effectively dividing the labor versus carrying most of the weight is a critical first step.

Start by considering: Are there any household tasks that you suspect can’t or won’t happen unless you take the lead? If so, consider why. Is it because your partner is doing something else that you don’t want to do, so the balance feels equal? Or is it because you feel like the only one who can do it? If it’s the latter, it’s worth recognizing that your help may actually be promoting a sense of learned helplessness. If you’re the one who typically plans the meals, and you like doing that -- that’s probably fine. But if you’ve taken on so much of the planning work that the one week you head out of town for a conference your partner orders takeout five nights in a row because they cannot conceive of how to meal plan and grocery shop accordingly -- well, that might be a sign of unhelpful dependency.

Now, maybe a string of take-out meals for a week doesn’t sound like it has major consequences to it, but there are some ways in which carrying all the weight can have significant detrimental outcomes. Dylan, for example, maintains the family calendar. Since he tracks the kids’ schedules, as well as his and Geoff’s, he’s got a pretty keen sense of the comings and goings. But when he had to shift priorities for three months caring for an ailing parent, lots of the daily duties and responsibilities fell to Geoff. Geoff’s difficulties with planning and time management led to late daycare pickups, arrival to soccer practices on the wrong dates, late fees on a few bills, and an uncomfortable increase in how much takeout the family lived on. When critical EF skills are underdeveloped, there can be meaningful physical, financial, and emotional costs as a result.

How To Rescue Yourself From Too Much Rescuing: Taking Meaningful Action

Dylan’s time caring for a parent really helped him see clearly just how much he’s been rescuing Geoff, rather than collaborating with him. So what does he do about it? Admittedly, this part can be tricky. The ideal next step here is an open, honest, and ego-less conversation of behavior. But, because human emotions are involved, things can often get uncomfortable. Geoff might react to Dylan’s observation about never prepping meals by pointing out that he never mows the lawn, and suddenly they’ve found themselves in a shouting match.

Perspective taking is a critical Executive Function skill to lean on at this point.

In Dylan’s case, the goals are for him to communicate his perspective on the EF workload imbalance effectively as well as seeking to understand the challenges Geoff faces when working on those areas. Using “I” statements can be an effective strategy (as opposed to using “you” statements) to communicate his perspective. In other words, Dylan’s more likely to make headway by saying “I feel frustrated that all meal planning is on my plate” than by saying “You never do any meal planning.” Following that with an invitation to share can shift the perspective from himself to Geoff: “What challenges do you anticipate if you tried to help me out with this?” And what Geoff reveals is really the key. If it’s thinking up meals that’s the issue, that requires one kind of strategy. If it’s planning out how long grocery shopping even takes, that requires something different.

If Dylan and Geoff can approach this EF-based challenge collaboratively, they can create a plan together that supports Geoff’s EF development in the process. As our coaches will tell you, it takes time to grow these skills. Therefore, the use of SMART goals could be integrated to help Geoff improve his planning. Perhaps he works from planning out one meal each week to eventually planning a full week and doing the shopping once a month. In addition, Dylan might share some specific strategies he uses; strategies that might seem obvious or intuitive to him could be meaningful once made explicit with Geoff. Perhaps he writes up the meal ideas first, creates a list of ingredients underneath, and then plugs those into an app (like this one or this one) that sorts the ingredients based on the store’s layout so as to avoid frantically running back to the dairy aisle because he forgot something.

In any case, be patient, hold your partner accountable, and in time you may be surprised by the shift you see. The potential for positive change is endless with the right support and approach.

Photo above by Albany Capture on Unsplash

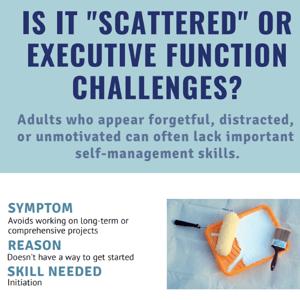

Download our infographic that describes 5 symptoms of Executive Function challenges in adults.