Editor's note: This week, we feature guest blogger Michael Keesler, J.D., Ph.D., a neuropsychologist who practices in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Please see his full bio below.

With spring’s arrival, parents and children are shaking off winter’s cabin fever and returning  outdoors. On the one hand, it is no great insight to observe that we enjoy spending time outdoors in nice weather. But there may be more to this phenomenon than we all know intuitively. Indeed, a growing body of research now supports what many of us in the mental health community have long suspected. This is simply that our mental and physical wellbeing actually relies upon interaction in and with nature.

outdoors. On the one hand, it is no great insight to observe that we enjoy spending time outdoors in nice weather. But there may be more to this phenomenon than we all know intuitively. Indeed, a growing body of research now supports what many of us in the mental health community have long suspected. This is simply that our mental and physical wellbeing actually relies upon interaction in and with nature.

This should not come as a big surprise, especially if we consider humans in terms of evolutionary history. Modern-day humans have existed for tens of thousands of years. Against that backdrop, the comforts of modern living are a new development on the timeline of human evolution. For the vast majority of our history, we were shaped by natural selection to exist in an environment that was outdoors, with unpredictable weather and varied temperatures, and organized by predator/prey relationships.

If you stop and think about it, modern living actually does much to insulate us from the effects of nature. For many of us, we sleep on large, soft, even rectangles of varying materials in climate-controlled rooms; we dress and bathe in air and water that is warmed to a pleasant temperature; we travel to school and work in climate-controlled vehicles with shock absorbers; we spend the day in climate-controlled rooms, bathed in even and unchanging lighting; we return home and spend the evening in climate-controlled and well-lit spaces; and we return to sleep on our soft rectangles to repeat the process again. If you think about it, this insulation from nature actually robs us and our children of opportunities to train executive function skills like impulse control (are these tasty-looking berries dangerous?); sustained attention (will I be ready when the fish takes the bait?); self-regulation and self-monitoring (will I be able to get back to safety before nightfall?); and complex problem-solving (how do I reach the high-hanging fruit?).

In an attempt to encapsulate the research literature, it is fair to say that urban living, modern technology, and separation from nature have been found to have negative effects on both mood and thinking skills. Fortunately, though, time spent in nature can help decrease and even reverse these effects. For those who may be curious, this intervention actually celebrates a long history. In Japan, it is called Shinrin-yoku, which is translated as “forest bathing.” In the West, the positive health effects of time spent at sanitoriums (remotely located hospitals for the chronically ill) are now thought to be attributed, at least in part, to the reconnection with nature.

Various studies have tried to quantify the extent to which time spent in nature can affect psychological and physiological health. Across those findings, it is fair to say that even 15 or 20 minutes per day spent in nature can have positive physical effects on things like blood pressure, pulse rate, nervous system activity, and cortisol (the “stress hormone”) levels. Time spent in nature can also have positive cognitive effects on attention (see also “Attention Restoration Theory”), self-discipline, impulse control, short-term memory, working memory, and concentration. Last, time with nature can help improve depression, anxiety, and the thought patterns that can characterize both.

So, with spring here, I encourage all readers to re-examine how they and their families can more consistently integrate nature into their lives. Walk in the park, the forest, along the beach, or by the river. If you have trouble walking, roll. If all else fails, have a seat in the grass (and leave the smartphone in your pocket). Talk to your children’s school and the parent-teacher association about the importance of time spent in nature. When possible, try to do paperwork and homework outdoors, perhaps at a picnic table. Volunteer as a family with local nature and conservation organizations. Explore commuting to work and school by walking or riding a bicycle. Go out in great weather, bad weather, and ho-hum weather. Watch the clouds go by. Stargaze. Your child’s Executive Function skills can likely benefit from spending more time in nature.

Resources

For details on the research supporting the above, I recommend Your Brain on Nature by Eva M. Selhub. An excellent free booklet from Children and Nature Network provides extensive information about how Executive Function skills in children can be developed through specific activities in nature. For more information on incorporating nature into one’s day-to-day life, check out http://wildernessawareness.org for their free and for-pay resources to help individuals on their “nature connection journey.” For readers in the United States, find your nearest national park at http://www.nps.org and view other outdoor activities at http://recreation.gov. Find hiking trails at http://www.hikingproject.com, http://www.alltrails.com, and http://www.trails.com.

Dr. Keesler is a clinical/forensic neuropsychologist who practices in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. He commutes to work by bicycle - daily, year-round, rain or snow or shine - to the only mild consternation of family and co-workers. His practice is predominantly neuropsychological assessment, where he diagnoses developmental disorders like learning disorders and ADHD, acquired injuries like traumatic brain injury, idiopathic disease like stroke or brain tumor, and degenerative disorders like dementia and multiple sclerosis. He believes strongly in the power of lifestyle change and adjunctive/alternative therapy as a first-line treatment for many common maladies of modern society. Visit his website at michaelkeesler.com or contact him at drmichaelkeesler@protonmail.

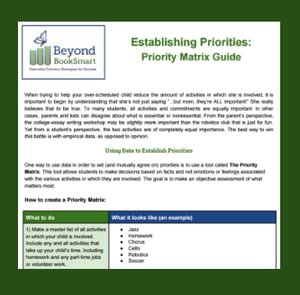

Does your child need help establishing priorities? Download our Priority Matrix Guide, a structured approach to helping an over-scheduled student identify what really matters.