We all want our children to genuinely love school. After all, we know there’s more to be gained from  schooling than memorizing times tables or reciting the state capitals. When children engage with caring teachers and other students, they acquire valuable experiences that help them grow socially and behaviorally - as well as academically. Unfortunately, when children start to associate school with negative feelings of frustration, anxiety, or isolation, it can lead to situations where they refuse to attend classes.

schooling than memorizing times tables or reciting the state capitals. When children engage with caring teachers and other students, they acquire valuable experiences that help them grow socially and behaviorally - as well as academically. Unfortunately, when children start to associate school with negative feelings of frustration, anxiety, or isolation, it can lead to situations where they refuse to attend classes.

Every few weeks, my morning as a school psychologist will start by assisting a reluctant student into the building. I typically receive an email or phone call from a parent explaining that their child has had an extremely difficult evening the night before, or is having a particularly anxious start to their day. I’ll guide the student into the building and to my office, offering a relaxation strategy to help them calm down and process their current feelings. Parents are often relieved to find out that once their child is in the building, it becomes much easier for them to transition into the classroom.

School refusal is becoming a hot topic of conversation among administrators, school psychologists, educators, and outside support personnel due to the serious long-term consequences associated with habitually missing school. This article seeks to assist parents in recognizing when their children are experiencing an atypical aversion to school and to provide them with strategies and resources to help get kids back on track.

Identification and Underlying Factors

School refusal can be distinguished from typical avoidance by a number of factors:

- How strongly the child resists

- How much distress is associated with attending school

- The duration of the avoidance

- How much the student’s resistance is impacting their (and their family’s) life

Students experiencing school refusal may present with a number of emotional, physical, and behavioral symptoms. Often, there is an underlying cause or condition contributing to the students’ behavior. Anxiety, for example, can take several forms. Students may experience one or more of the following: separation anxiety, social anxiety, or performance anxiety. They may be experiencing other psychiatric disorders such as Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder, Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder, or Depression. Students may refuse to attend all or part of the school day as a way to escape unpleasant situations like ongoing bullying, or to gain attention from parents or caregivers.

What to Watch for

It is crucial to watch out for the following characteristics of a developing problem so that prompt action can be taken at home and school:

- Frequent unexcused absences, tardiness, or dismissals

- Absences on significant days (tests, speeches, physical education class)

- Resistance to getting out of bed in the morning with no signs of medical illness

- Increased complaints of physical symptoms such as stomach aches, headaches, muscle tension, shortness of breath, or nausea and vomiting

- Behavioral symptoms such as clinging or refusing to separate from a caregiver, crying or tantrums, and/or failure to complete homework

- Frequent calls or texts to parents throughout the school day

Intervention Strategies for School Refusal

Team Approach

When teachers or parents suspect that a student’s lack of attendance is due to social-emotional concerns, they should take immediate action and support the child with a team based approach. Setting up an informal meeting to address home and school concerns is often the best first step. Frequent communication between home and school can assist in recognizing patterns to identify the cause of stress for the student as well as pinpoint the antecedents and consequences (what happens before and after) of the refusal. Effective remediation strategies are dependent on the source of the child’s need and a gradual re-entry plan may need to be developed based on the severity of school refusal and the age of the student. Such plans allow students to attend a portion of the school day initially with a gradual increase in the length of time spent at school. Some schools also have programs within the building to serve as a home base for students who are not yet ready to return to the classroom, but feel comfortable enough to complete work in a more supportive, smaller setting. Other accommodations that could be helpful include providing alternatives to group work or public speaking presentations for students experiencing school phobia or performance anxiety and providing options (classwork in a different setting or utilizing a coping strategy for ten minutes) for students with generalized anxiety.

Emotional Support

It’s important for students experiencing signs of school refusal to develop a close relationship with at least one support staff person at their school (guidance counselor, school psychologist, school adjustment counselor) as their go-to place for expressing their feelings and developing individual strategies to combat anxiety, regulate emotions, and effectively transition back into the classroom. In addition to learning coping strategies, having a safe space at school helps students develop self-advocacy and problem-solving skills. Students and families who prefer outside counseling are encouraged to seek private counseling options that fit best with their schedule. Counseling support often focuses on developing positive self-talk, educating students about mental health and the intersection between thoughts, emotions and behaviors, and practicing calming strategies like deep breathing, progressive muscle relaxation, and guided imagery. Open communication between families and children is also encouraged so that concerns about peer conflicts, social pressures, academic difficulties, and worries can be expressed in a supportive, loving environment.

School refusal can heighten at various points of a child’s development, with episodes occurring most often during times of transition, such as the start of kindergarten, middle, or high school. A comprehensive evaluation by a school or private mental health professional is often the best avenue to determine if there is an underlying academic or emotional cause for your child’s aversion to school. Being proactive and recognizing the signs and symptoms as they develop is the most important part of implementing strategies to remedy the situation because typically, the longer a child misses school and interrupts their routine, the harder it is for them to adjust and adapt back into the school environment. It's good to keep in mind that many students can successfully return to school when the right supports are in place.

Michelle Leach, M.A., C.A.G.S. is an Executive Function coach with Beyond BookSmart and a school psychologist in Massachusetts. After earning her bachelor's degree at Emory University in Atlanta, GA, Michelle completed her graduate studies at Rhode Island College, earning a Master's Degree in Educational Counseling and a Certificate of Advanced Graduate Study in School Psychology. Michelle has experience working with children of varying ages and abilities. She currently works in a Massachusetts public middle school where she supports students’ social-emotional, behavioral, Executive Function, and academic difficulties. Michelle believes that student success is an individualized process achieved through collaboration and consistency between the student, family, school, and community.

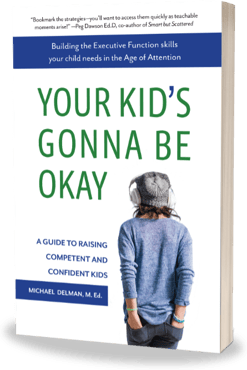

Looking for more parenting tips and strategies to help your child be successful in school and beyond? Michael Delman's book Your Kid's Gonna Be Okay: Building the Executive Function Skills Your Child Needs in the Age of Attention is now available for pre-order. Download a free excerpt below.